Sunday, March 19, 2017

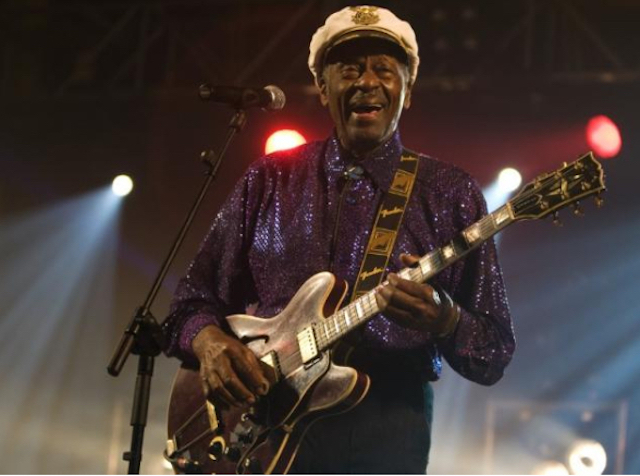

Rock ‘n’ roll pioneer Chuck Berry dead at 90

Chuck Berry, who duck-walked his way into the pantheon of rock ‘n’ roll pioneers as one of its most influential guitarists and as the creator of raucous anthems that defined the genre’s early sound and heartbeat, died on Saturday at his Missouri home. He was 90.

Police in St. Charles County, outside St. Louis, said they were called to Berry’s home by a caretaker who reported he had fallen ill, and emergency responders found the performer unconscious. Emergency medical technicians tried to revive him with cardiopulmonary resuscitation, to no avail, and Berry was pronounced dead at 1:26 p.m. local time, police said.

Although Elvis Presley was called the king of rock ‘n’ roll, that crown would have fit just as well on the carefully sculpted pompadour of Charles Edward Anderson Berry. He was present in rock’s infancy in the 1950s and emerged as its first star guitarist and lyricist.

Berry hits such as “Johnny B. Goode,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Maybellene” and “Memphis” melded elements of blues, rockabilly and jazz into some of America’s most timeless pop songs of the 20th century.

He was a monumental influence on just about any kid who picked up a guitar with rock star aspirations – Keith Richards, Paul McCartney, John Lennon and Bruce Springsteen among them.

Bob Dylan called Berry “the Shakespeare of rock ‘n’ roll,” and he was one of the first popular acts to write as well as perform his own songs. They focused on youth, romance, cars and good times, with lyrics that were complex, humorous and sometimes a little raunchy.

Both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones, as well as the Beach Boys and scores of other acts – even Elvis – covered Berry’s songs.

“If you tried to give rock ‘n’ roll another name,” Lennon once said, “you might call it ‘Chuck Berry’.”

When Richards inducted Berry into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, he said: “It’s very difficult for me to talk about Chuck Berry because I’ve lifted every lick he ever played. This is the gentleman who started it all.”

Berry’s legacy as one of rock’s founders was tarnished by his reputation as a prickly penny-pincher and run-ins with the law, including sex-related offenses after he achieved stardom.

Marking his 90th birthday in 2016 by announcing he would release his first album in 38 years, Berry listed T-Bone Walker, Carl Hogan of Louis Jordan’s band and Charlie Christian from Benny Goodman’s band as his guitar influences, but his lyrical style was all his own. Punchy wordplay and youth-oriented subject matter earned him the nickname “the eternal teenager” early in his career.

Berry came along at a time when much of the United States remained racially segregated, but it was hard for young audiences of any color to resist a performer who delivered such a powerful beat with so much energy and showmanship.

KEY COLLABORATOR

Berry said he performed his signature bent-knee, head-bobbing “duck walk” across more than 4,000 concert stages. He said he invented the move as a child in order to make his mother laugh as he chased a ball under a table.

Some critics suggested it was his former pianist, Johnnie Johnson, who composed the tunes while Berry only penned the lyrics. Johnson sued Berry in 2000 for song royalties, saying they were equal collaborators on many of the hits, but the case was dismissed on grounds that the statute of limitations had expired.

It was with Johnson that Berry first made his mark, playing at black clubs in the St. Louis area at the musically ripe age of 27. Berry started out filling in with Johnson’s group, known as Sir John’s Trio, in 1953, and Johnson eventually acknowledged Berry’s talent, charisma and business acumen by allowing the group to evolve into the Chuck Berry Trio.

At the suggestion of blues legend Muddy Waters, Berry auditioned for Chess Records, the white-owned Chicago label that put out scores of blues hits. The result was the rockabilly tune “Ida Red,” which became a hit after it was retitled “Maybellene” and discovered by white audiences.

When the record came out, Berry said he was stunned to see that pioneering rock ‘n’ roll disc jockey Alan Freed and another man he had never met, Russ Fratto, were listed as co-writers of “Maybellene.”

The shared credits deprived him of some royalty payments, but Berry dismissed it at the time as part of the “payola” system that determined which records got radio play in the 1950s. He later regained all the rights to his compositions.

ONLY ONE NO. 1 HIT

Berry and Johnson collaborated for some 30 years on such rock anthems as “School Days,” “Roll Over Beethoven,” “Back in the U.S.A.,” “Reelin’ and Rockin’,” “Rock & Roll Music,” “No Particular Place to Go,” “Memphis” and “Sweet Little Sixteen.” But Berry’s only No. 1 hit was “My Ding-a-Ling,” a throwaway novelty song that seemed to be a juvenile sex reference.

Berry’s reputation for being greedy and grouchy was evident in the 1987 documentary “Hail! Hail! Rock and Roll,” which focused on a 60th-birthday concert that Keith Richards organized for him. The movie’s makers said Berry refused to show up for filming each day unless given a bag of cash.

“He was an oddly cheap character in some ways,” Rolling Stones singer Mick Jagger told Mojo magazine. “He … was always rude to everyone. He became too much of a parody of himself.”

Berry was born Oct. 18, 1926, the third of six children whose father was a contractor and church deacon and whose mother was a schoolteacher. They lived in a relatively prosperous black section of St. Louis known as the Ville.

In the first of his brushes with the law, Berry was sent to a reformatory as a teenager for armed robbery. After his release at age 21, he worked in an auto plant and as a photographer and trained to be a hairdresser.

As he became a star, Berry irked some in St. Louis by acquiring property in a previously white area and opening his own nightclub, where another legal scrape nearly ended his career.

At a show in Texas in 1959, Berry had met a 14-year-old Native American girl and hired her to work at the St. Louis club. She was later fired and then arrested on a prostitution charge, which led to Berry being convicted for violating the Mann Act, transporting a woman across state lines for immoral purposes. He was sent to prison in 1962 for a year and a half and wrote several songs while incarcerated, including “No Particular Place to Go.”

Berry had more trouble in 1979 when he was convicted of tax evasion, serving four months in prison, and in the 1990s when a number of women accused him of videotaping them in the bathrooms of his restaurant-club in Wentzville, Missouri.

While the hits did not keep coming for Berry, the tributes never stopped, and he continued playing a monthly show at a St. Louis nightclub into his late 80s. He received a Grammy award for lifetime achievement in 1984 and his 1986 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame made him part of the inaugural class.

Illustrating his influence, a recording of “Johnny B. Goode” was included in a collection of music sent into space aboard the unmanned 1977 Voyager I probe to provide aliens a taste of Earth culture.

Despite his reputation as a womanizer, Berry and his wife, Toddy, were married more than 60 years.

source: interaksyon.com